16 Model Comparison

We have acquired knowledge on constructing models and evaluating their performance. However, the challenge lies in selecting the “optimal” model from a pool of potential candidates. Some may think that we can employ metrics like the Coefficient of Determination (\(\mbox{R}^2\)) to compare and choose superior models; however, a predicament arises because these metrics tend to favor models with a larger number of explanatory variables, even if some of those variables are actually irrelevant and do not contribute meaningfully to the model’s effectiveness. In this Chapter, I introduce some popular methods to balance the trade-off between a goodness of fit and model’s complexity.

Key words: adjusted \(\mbox{R}^2\), likelihood ratio test, Akaike’s Information Criterion

16.1 Model Fit and Complexity

In the field of biological sciences, it is common to encounter multiple hypotheses or the need for exploratory analysis. In such instances, it becomes necessary to develop various models, each corresponding to a specific hypothesis, and subsequently compare their respective performances. The crucial aspect lies in how we quantify the “performance” of these models, acknowledging that this term can be somewhat ambiguous. As the determination of model performance ultimately dictates which model is superior, it profoundly impacts the conclusions drawn from the research. Thus, the significance of this process cannot be overstated.

One potential approach is to utilize the Coefficient of Determination (Chapter 12) as a measure of model performance. These metrics provide an indication of the proportion of variation in the response variable that is explained by the model, making them reasonable options. However, there are situations where these measures are not meaningful for model comparison.

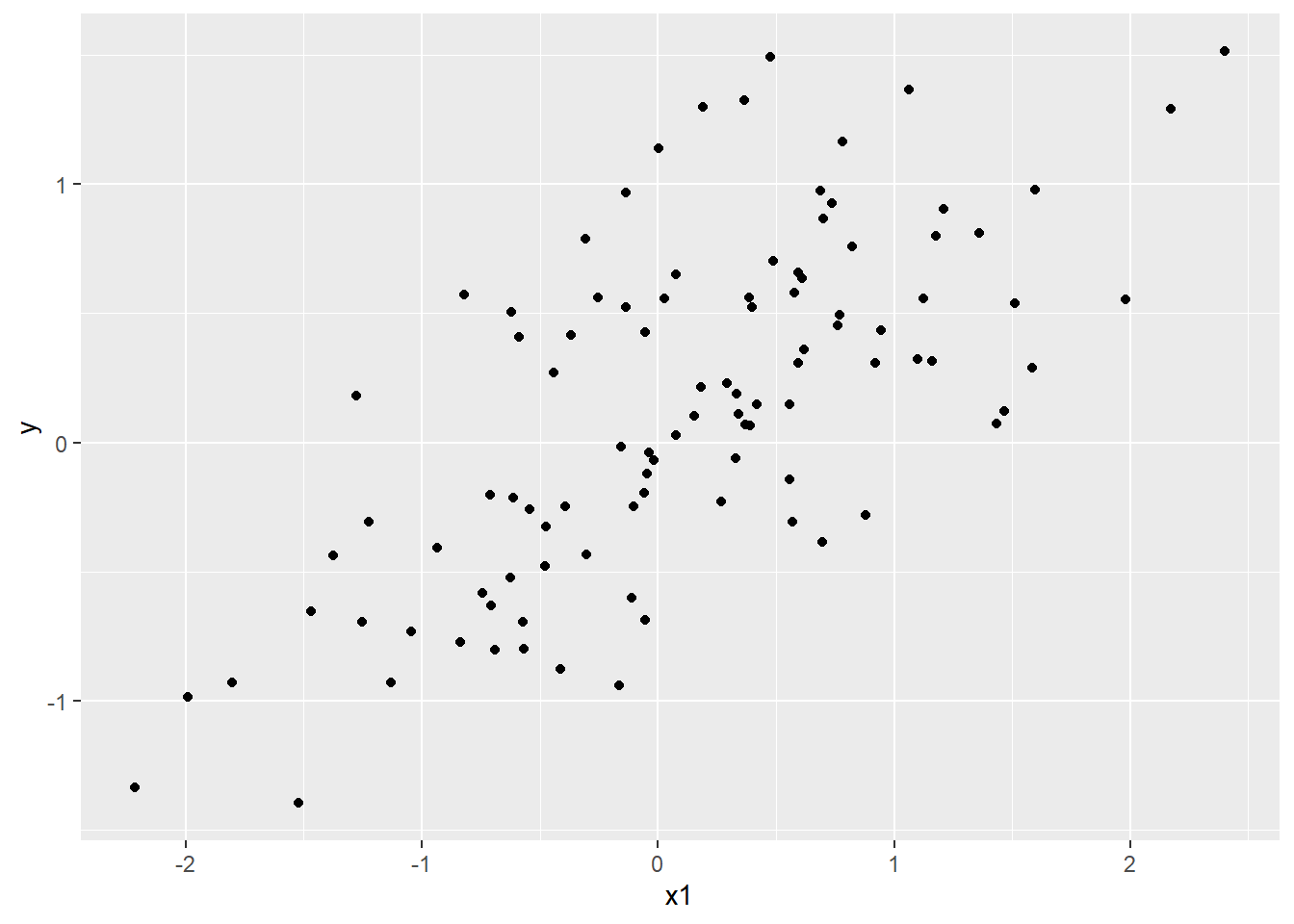

To illustrate this, let’s consider the following simulated data. The advantage of using simulated data is that we already know the correct outcomes, enabling us to validate and verify the analysis results.

set.seed(1) # for reproducibility

# hypothetical sample size

n <- 100

# true intercept and slope

b <- c(0.1, 0.5)

# hypothetical explanatory variable

x1 <- rnorm(n = n, mean = 0, sd = 1)

# create a design matrix

X <- model.matrix(~x1)

# expected values of y is a function of x

# %*% means matrix multiplication

# y = X %*% b equals y = b[1] + b[2] * x

# recall linear algebra

y_hat <- X %*% b

# add normal errors

y <- rnorm(n = n, mean = y_hat, sd = 0.5)

# plot

df0 <- tibble(y = y, x1 = x1)

df0 %>%

ggplot(aes(y = y,

x = x1)) +

geom_point()

Figure 16.1: Simulated data

The above code generated the response variable, denoted as \(y\), as a function of the variable \(x_1\) (\(y_i = \beta_0 + \beta_1 x_1 + \varepsilon_i\)). The values of the intercept and slope were set to 0.1 and 0.5 respectively. Given our knowledge of how this data was generated, we can establish the “correct” model. Now, let’s assess the performance of this model:

##

## Call:

## lm(formula = y ~ x1, data = df0)

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -0.93842 -0.30688 -0.06975 0.26970 1.17309

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) 0.08115 0.04849 1.673 0.0974 .

## x1 0.49947 0.05386 9.273 4.58e-15 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 0.4814 on 98 degrees of freedom

## Multiple R-squared: 0.4674, Adjusted R-squared: 0.4619

## F-statistic: 85.99 on 1 and 98 DF, p-value: 4.583e-15The estimated values for the intercept and slope of the model are approximately 0.08 and 0.5 respectively, which are reasonably close to the true values. The coefficient of determination, indicating the proportion of variation in the response variable explained by the model, is 0.467.

Now, let’s consider the scenario where we include another variable, x2, that is completely irrelevant.

# add a column x2 which is irrelevant for y

df0 <- df0 %>%

mutate(x2 = rnorm(n))

# add x2 to the model

m2 <- lm(y ~ x1 + x2, data = df0)

summary(m2)##

## Call:

## lm(formula = y ~ x1 + x2, data = df0)

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -0.92274 -0.32325 -0.07538 0.26640 1.16629

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) 0.08178 0.04870 1.679 0.0963 .

## x1 0.49996 0.05408 9.244 5.75e-15 ***

## x2 -0.02294 0.04697 -0.488 0.6264

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 0.4833 on 97 degrees of freedom

## Multiple R-squared: 0.4687, Adjusted R-squared: 0.4577

## F-statistic: 42.78 on 2 and 97 DF, p-value: 4.793e-14Surprisingly, the \(\mbox{R}^2\) value has increased to 0.469 even though the model includes the unnecessary variable.

This outcome occurs because the \(\mbox{R}^2\) value does not consider the complexity of the model or the number of parameters employed. In fact, if we can increase the number of parameters indefinitely, it’s easy to construct a model with an \(\mbox{R}^2\) value of \(1.00\). This is achieved by assigning \(N\) parameters to \(N\) data points, effectively making the parameters equivalent to the response variable itself. However, this approach is undesirable since the model essentially explains the response variable with the response variable (\(y = y\)), which is self-evident. Therefore, if we aim to develop a meaningful model, it is essential to employ alternative measures for model comparisons.

16.2 Comparison Metrics

While various measures exist to evaluate model performance, I will discuss three fundamental ones: Adjusted \(\mbox{R}^2\), the likelihood ratio test, and Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC). The first two focus on how well the model fits the available dataset while appropriately considering model complexity. On the other hand, AIC assesses the model’s capability to make predictions on unseen data (“out-of-sample” prediction). There is no universally optimal measure — it depends on the specific research objective. If the goal is to assess the model’s fit to the current data, any of the first two measures or other similar ones can be used. However, if evaluating the model’s predictive ability is the objective, AIC should be employed. The crucial factor to consider is that when comparing models, it is essential to ensure that:

- The models use the same dataset. Models fitted to different data sets cannot be compared by no means.

- They assume an identical probability distribution among candidate models. For example, a normal model cannot be compared with a Poisson model.

I will now describe the rationale behind each method.

16.2.1 Adjusted \(\mbox{R}^2\)

The Adjusted \(\mbox{R}^2\) is a natural extension of the ordinary \(\mbox{R}^2\). The original formula for \(R^2\) is:

\[ R^2 = 1 - \frac{SS}{SS_0} \]

Here, \(SS\) represents the sum of squares of residuals (\(\sum \varepsilon_i\)), and \(SS_0\) represents the sum of squares of the response variable (\(\sum (y_i - \mu_y)\), where \(\mu_y\) is the sample mean of \(y\)). The Adjusted \(R^2\) modifies this formula to account for the number of parameters used:

\[ \begin{align*} \text{Adj. }R^2 &= 1 - \frac{SS/(N-k)}{SS_0/(N-1)} \\ &= 1 - \frac{\sigma^2_{\varepsilon}}{\sigma^2_0} \end{align*} \]

In the equation above, \(k\) denotes the number of parameters utilized in the model. Hence, the numerator indicates the residual variance of the model, \(\sigma^2_{\varepsilon}\), while the denominator represents the variance of the response variable, \(y\). We can obtain these values from the model objects m1 and m2:

## [1] 0.4619164## [1] 0.4577026Now we can observe that the model m2 exhibits a lower value of the adjusted \(\mbox{R}^2\). This discrepancy arises because the adjusted \(\mbox{R}^2\) incorporates a penalty term for the inclusion of additional explanatory variables (\(k\)). In order for the adjusted \(\mbox{R}^2\) to decrease, the variable x2 must significantly decrease \(\sigma^2_{\varepsilon}\) beyond what would be expected by chance alone. In other words, x2 needs to provide a substantial improvement in explaining the response variable to counterbalance the penalty imposed by the inclusion of an extra variable.

Note that both \(\mbox{R}^2\) and \(\mbox{Adj. R}^2\) are applicable only to normal models. In the case of the GLM framework (Chapter 14), we utilize a different measure called \(\mbox{R}^2_D\), where \(D\) represents “deviance.” Deviance (\(D\)) is defined as the negative twice the log-likelihood. We estimate \(\mbox{R}^2_D\) using the deviance (\(D\)), which is comparable to the traditional \(\mbox{R}^2\) but tailored for GLMs.

\[ \begin{align} \mbox{R}^2_D &= 1 - \frac{-2 \ln L}{-2 \ln L_0}\\ &= 1 - \frac{D}{D_0} \end{align} \]

In the above formula, \(L\) (\(L_0\)) represents the likelihood of the fitted (null) model, while \(D\) (\(D_0\)) represents the deviance. There are several substitutes available for \(\mbox{Adjusted R}^2\). One such method, known as McFadden’s method 6, incorporates model complexity into the calculation using the following formula:

\[ \mbox{Adj. R}^2_{D} = 1 - \frac{\ln L - k}{\ln L_0} \]

16.2.2 Likelihood Ratio Test

Another possible approach is the likelihood ratio test, a statistical test used to compare the fit of two nested models. It calculates the log ratio of likelihoods of the two models to as a test statistic:

\[ \begin{align} \mbox{LR} &= -2 \ln \frac{L_0}{L_1}\\ &= -2 (\ln L_0 - \ln L_1) \end{align} \]

The likelihoods of the null and alternative models are denoted as \(L_0\) and \(L_1\) respectively. Under the null hypothesis, the test statistic \(\mbox{LR}\) follows a chi-square distribution, if the sample size approaches infinity. This enables us to determine whether the inclusion of a new variable (or variables) has significantly enhanced the model’s likelihood beyond what would be expected by chance.

We employ this approach because likelihood encounters a problem similar to \(\mbox{R}^2\). The log likelihood of the models can be obtained using the logLik() function:

# log likelihood: correct model

logLik(m1)## 'log Lik.' -67.77319 (df=3)

# log likelihood: incorrect model

logLik(m2)## 'log Lik.' -67.6504 (df=4)The model m2 has a higher likelihood because likelihood is an absolute measure of model performance. However, the likelihood ratio test overcomes this limitation by comparing the observed increase in likelihood with what would be expected by chance. The test statistic \(\mbox{LR}\) follows a chi-square distribution7, which serves as a reference distribution. The chi-square distribution has a single parameter - degrees of freedom - which, in this case, corresponds to the difference in the number of model parameters used.

The model m1 utilized two parameters (intercept and one slope), whereas the model m2 employed three parameters (intercept and two slopes). Consequently, the test statistic is assumed to follow a chi-square distribution with one degree of freedom. While it is possible to calculate the p-value manually, the anova() function can perform this analysis:

# test = "Chisq" specifies a chi-square distribution

# as a distribution of LR

anova(m1, m2, test = "Chisq")## Analysis of Variance Table

##

## Model 1: y ~ x1

## Model 2: y ~ x1 + x2

## Res.Df RSS Df Sum of Sq Pr(>Chi)

## 1 98 22.709

## 2 97 22.653 1 0.055702 0.6253The Pr(>Chi) value, which represents the p-value, is significantly greater than 0.05. This indicates that the inclusion of variable x2 does not improve the model’s likelihood than what would be expected by chance.

The likelihood ratio test can be applied to a wide range of models as long as they are capable of estimating likelihood. Therefore, this method is highly versatile. However, one limitation is that the competing models must be nested, meaning that the null model should be a subset of the alternative model. In the example provided, m1 includes only the explanatory variable x1, while m2 incorporates both x1 and x2. However, m1 can be viewed as a special case of m2 where the slope of x2 is fixed at zero. Thus, m1 can be considered as a “nested” subset of m2.

16.2.3 AIC

The AIC takes a different approach to evaluating model performance compared to other measures. While measures like \(\mbox{R}^2\) primarily assess the goodness of fit to the available dataset used for model fitting, the AIC is rooted in the information theoretic perspective. It evaluates a model’s ability to predict unseen data from the same population.

The mathematical details of AIC are beyond the scope of this discussion, but for those interested, reference Burnham and Anderson 2002. However, it is crucial to understand that the AIC differs fundamentally from other measures as it assesses the model’s robustness when new data is added.

Despite the underlying mathematical complexity, the AIC formula is remarkably simple:

\[ \mbox{AIC} = 2k - 2\ln L \]

Here, \(k\) represents the number of model parameters, and \(L\) is the likelihood. Lower AIC values indicate better predictability of the model. The formula consists of two terms: the first term is twice the number of parameters, and the second term is the model’s deviance. Thus, a lower AIC value is preferred. While one might perceive it as a variant of \(\mbox{R}^2\) or similar measures, it is important to note that the penalty term in AIC was derived from the Kullback–Leibler divergence.

As evident from the formula, AIC can be estimated for any model that has a valid likelihood, making this method widely applicable, including for GLMs. In R, the model’s AIC can be computed using the AIC() function.

# AIC: correct model

AIC(m1)## [1] 141.5464

# AIC: incorrect model

AIC(m2)## [1] 143.3008The AIC value for m2 is higher, indicating that the second model has a lower capability to predict unseen data. AIC has several valuable features that make it a useful criterion. For instance, unlike likelihood tests, it can be used to compare more than two models. Moreover, in the field of biological sciences, where prediction often holds significant interest, AIC is particularly relevant. For example, it helps determine which model performs best when predicting unobserved sites within the same study region. AIC suggests that the selected “parsimonious” model with the lowest AIC would provide the best performance among the competing models. Consequently, AIC finds widespread use in biology, especially in ecology.

However, it is important to exercise caution when interpreting the results. Specifically:

The model with the lowest AIC does not necessarily imply it is the “true” model. We are limited to the explanatory variables we have collected, and AIC can only indicate which model is better among the choices available. It is possible that all the candidate models are incorrect.

AIC is not designed to infer causal mechanisms. Variables that are not causally related may enhance the model’s ability to predict unseen data. If the goal is causal inference, a different criterion, such as the backdoor criterion, should be employed. For example, AIC is not suitable for analyzing controlled experiments aimed at uncovering causal mechanisms in biology.

There is often misuse of this metric, particularly in overlooking the second component (see arguments in Arif and MacNeil 2022). Therefore, it is crucial to clearly define the objective of your analysis to ensure the appropriate choice of statistical methods.

16.3 Laboratory

16.3.1 Format Penguin Data

The R package palmerpenguins provides penguin data that were collected and made available by Dr. Kristen Gorman and the Palmer Station, Antarctica LTER, a member of the Long Term Ecological Research Network. To get started, install this package onto your computer:

# Perform only once

# install.packages("palmerpenguins")

library(palmerpenguins)For this exercise, we will use the penguins_raw dataset. However, the dataset is not well-organized and may be prone to errors in its current format. Before delving into data analysis, let’s perform the following tasks:

Column names are a mix of upper and lower cases, and they contain white spaces. We need to format the column names as follows: (1) convert all characters to lowercase, (2) replace white spaces with underscores

_, and (3) remove parentheses (e.g.,(mm)). To accomplish this, we can useclean_names()function fromjanitorpackage. You can check their usage by typing?function_namein the R console.In the following exercise, we will focus on the data in the

Clutch Completioncolumn, which records data asYesorNo. To make it more suitable for analysis, we need to convert this information to binary values:1forYesand0forNo. Useifelse()function in combination withmutate().The

Speciescolumn in the dataset contains species names such as Adelie Penguin (Pygoscelis adeliae), Chinstrap penguin (Pygoscelis antarctica), Gentoo penguin (Pygoscelis papua). We need to convert these species names to standardized ones, specifically:adelie,chinstrap, andgentoo. Use of thedplyr::mutate()anddplyr::case_when()functions for this task.Lastly, we should remove any rows that contain missing values (

NA) in the columnsCulmen Length (mm),Culmen Depth (mm),Flipper Length (mm),Body Mass (g), andSex. To achieve this, we can utilize thedplyr::drop_na()function.

16.3.2 Analyze Penguin Data

After formatting the data, our next step is to perform the following:

Develop a statistical model that explains

Clutch Completionusing the variablesSpecies,Culmen Length (mm),Culmen Depth (mm),Flipper Length (mm),Body Mass (g), andSex. Use an appropriate probability distribution for this model.Perform an AIC-based model selection using the

MuMIn::dredge()function. This process will help us identify the variables that are most important for predicting the clutch completion status.