17 Generalized Linear Mixed Effect Model

In the previous chapters, we developed foundational skills in linear modeling, including generalized linear models (GLMs). GLMs are a powerful and flexible framework when data arise from a single, relatively homogeneous set of observational units. However, ecological and biological data are often structured into multiple groups that differ in their underlying characteristics (e.g., sites, individuals, years). When such hierarchical or grouped structure is present, generalized linear mixed-effects models (GLMMs) provide a natural extension of GLMs by explicitly accounting for both shared population-level effects and group-specific variation.

Learning Objectives:

Understand group structure in biological data

Understand random intercept and slope

Understand when random effects are preferred over fixed effects

pacman::p_load(tidyverse,

lme4,

glmmTMB)17.1 Group Structure

In ecological studies, data are often collected in a hierarchical or grouped structure rather than as independent observations. For example, measurements may be repeated across sites within watersheds, individuals within populations, or years within study locations.

Let’s use Owls dataset from the R package glmmTMB to grasp the idea of how it works. This dataset is originally published in Roulin and Bersier 2007, Animal Behavior.

This dataset contains observations on begging behavior of barn owl nestlings across different experimental conditions. The data come from a study investigating sibling negotiation—a vocal communication system where nestlings use calls to peacefully resolve which individual will receive the next food item delivered by parents.

The experiment manipulated hunger levels by either food-depriving or satiating nestlings, then recorded their negotiation calls during parental arrivals. This allowed researchers to test whether negotiation intensity honestly signals hunger and whether nestlings adjust their calling based on which parent (male or female) arrives at the nest. The dataset includes repeated observations across 27 nests over time, in each of which the researchers counted negotiation calls by individual chick - thus, the data has a group (or nested) structure (599 observations at the individual level, nested within 27 nests).

It has seven main columns:

Nest, a factor identifying each of the 27 individual nests.FoodTreatment, indicating whether the nestlings were experimentally “Deprived” (kept hungry before observation) or “Satiated” (fed before observation).SexParent, identifying whether the provisioning parent was “Male” or “Female.”ArrivalTime, the time when the parent arrived at the nest.SiblingNegotiation, the number of negotiation calls made by siblings (the primary response variable).BroodSize, the number of chicks in the nest.NegPerChick, the number of negotiations per chick.

Since this original data contains a mix of upper- and lower-case letters, we will first clean the format:

(df_owl <- df_owl_raw %>% # Start with raw owl dataset and assign cleaned version

janitor::clean_names() %>% # Standardize column names (lowercase, underscores, etc.)

mutate(across(.cols = where(is.factor), # Select all factor-type columns

.fns = str_to_lower)) # Convert factor levels to lowercase

) ## # A tibble: 599 × 8

## nest food_treatment sex_parent arrival_time sibling_negotiation brood_size

## <chr> <chr> <chr> <dbl> <int> <int>

## 1 autava… deprived male 22.2 4 5

## 2 autava… satiated male 22.4 0 5

## 3 autava… deprived male 22.5 2 5

## 4 autava… deprived male 22.6 2 5

## 5 autava… deprived male 22.6 2 5

## 6 autava… deprived male 22.6 2 5

## 7 autava… deprived male 22.8 18 5

## 8 autava… satiated female 22.9 4 5

## 9 autava… deprived male 23.0 18 5

## 10 autava… satiated female 23.1 0 5

## # ℹ 589 more rows

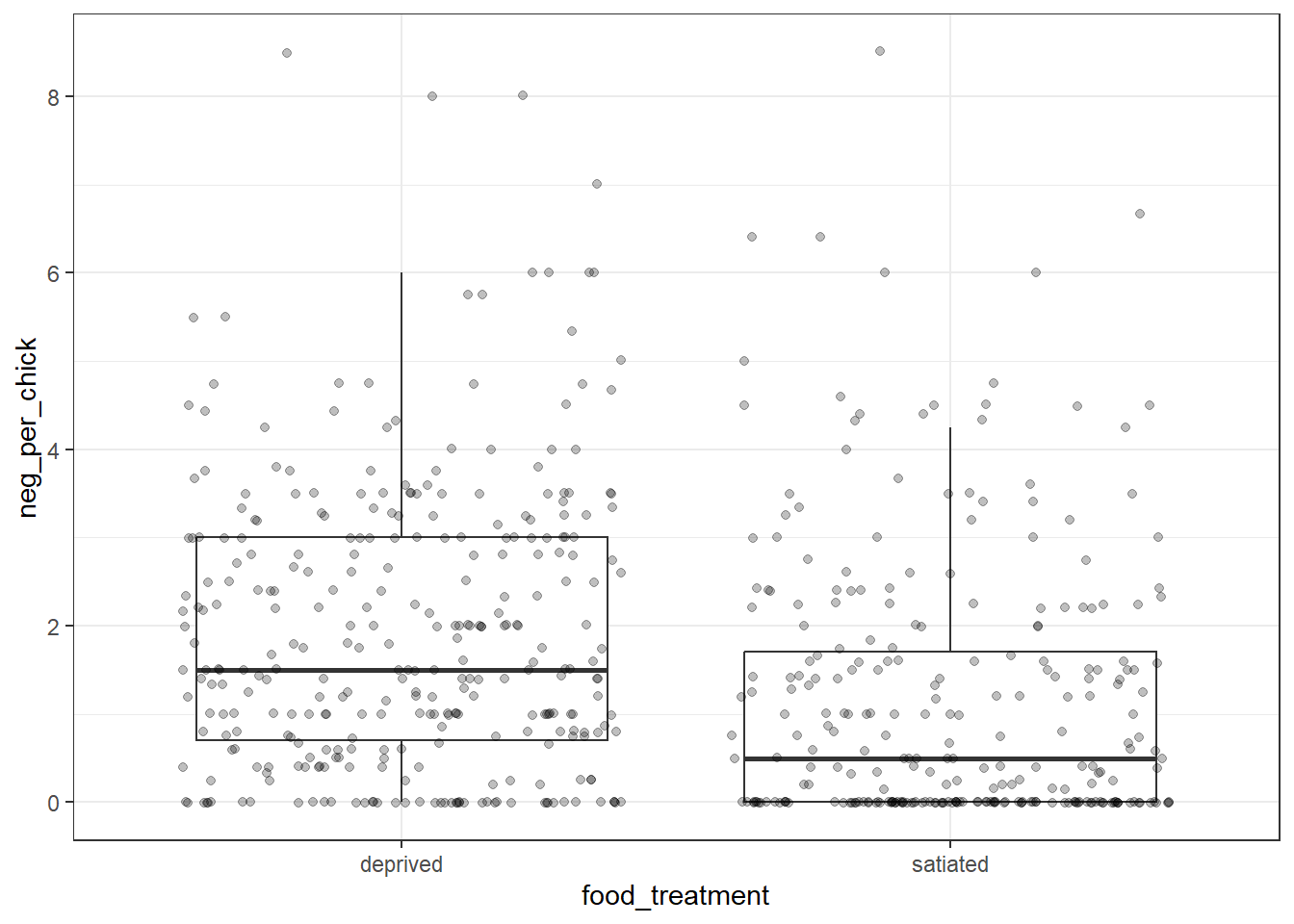

## # ℹ 2 more variables: neg_per_chick <dbl>, log_brood_size <dbl>Then, visualize the data. Our primary interest here is whether food_treatment changed the number of negotiations per chick (neg_per_chick = sibling_negotiation / brood_size):

df_owl %>% # Use cleaned owl dataset

ggplot(aes(x = food_treatment, # Map food treatment to x-axis

y = neg_per_chick)) + # Map number of negatives per chick to y-axis

geom_boxplot(outliers = FALSE) + # Draw boxplots without plotting outliers

geom_jitter(alpha = 0.25) + # Add jittered raw data points with transparency

theme_bw() # Apply a clean black-and-white theme

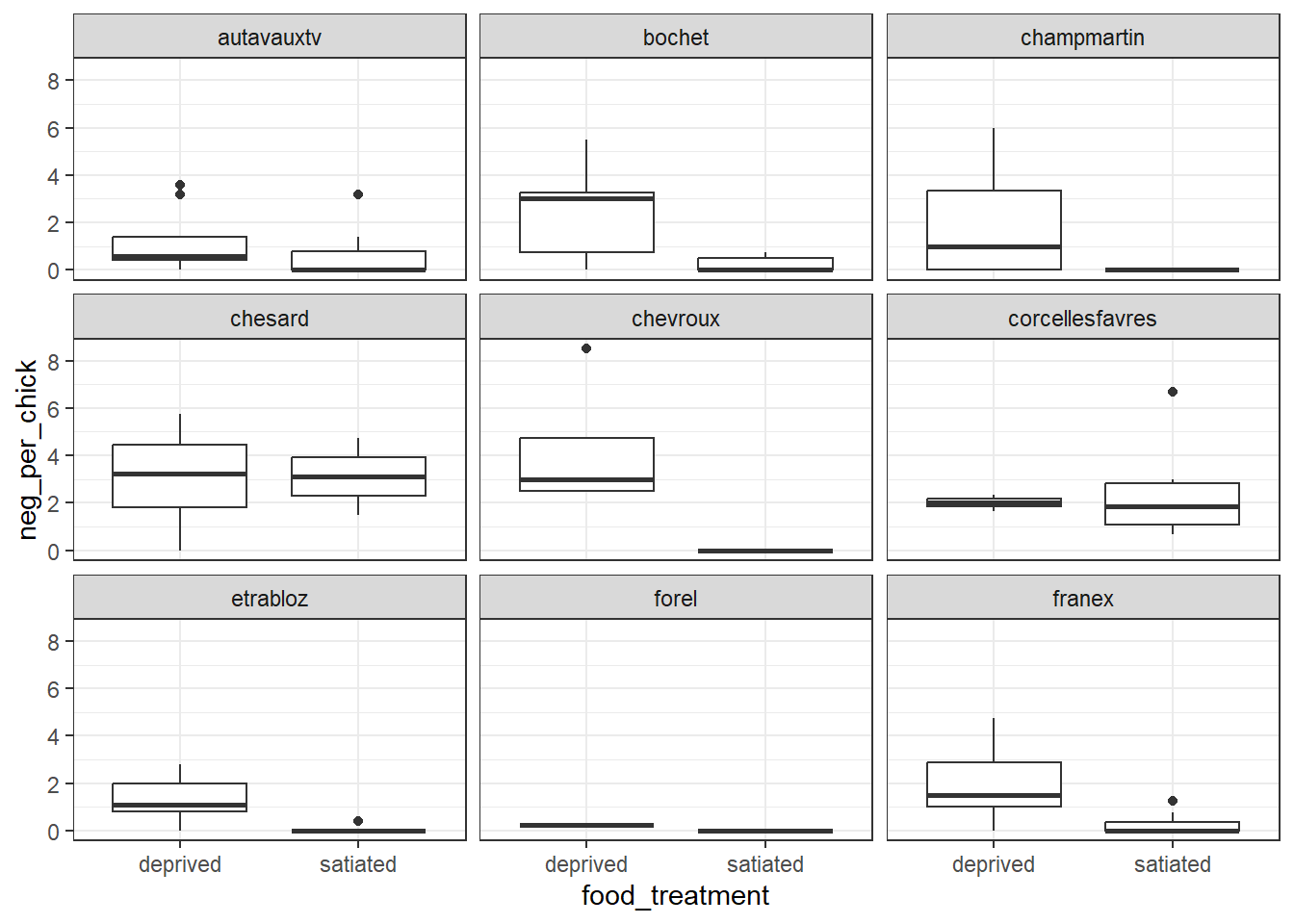

At first glance, the figure appears straightforward: the number of negotiations per chick decreases when nestlings are satiated. However, a closer examination reveals an important additional complexity in the data—its grouped structure. The example below highlights the first nine nests, illustrating substantial variation in neg_per_chick among nests.

v_g9 <- unique(df_owl$nest)[1:9] # Extract first 9 nest IDs

df_owl %>% # Start with owl dataset

filter(nest %in% v_g9) %>% # Keep only observations from selected nests

ggplot(aes(x = food_treatment,

y = neg_per_chick)) +

geom_jitter(alpha = 0.25, # Draw jitter plots for each treatment

width = 0.1) +

facet_wrap(facets =~ nest, # Create separate panels for each nest

ncol = 3, # Arrange panels into 3 columns

nrow = 3) + # Arrange panels into 3 rows

theme_bw() # Apply clean black-and-white theme

To examine the effect of food treatment while accounting for differences among nests, the GLM can be specified as follows:

# Response: sibling_negotiation — raw count of negotiation calls

# Predictors: food_treatment and nest

# Offset: log(brood_size)

# Note: Including this offset models the log rate of negotiations per chick,

# i.e., log(sibling_negotiation / brood_size), which is equivalent to neg_per_chick

# check mean and variance of the response

# (mu_y <- mean(df_owl$sibling_negotiation)) # 6.72

# (var_y <- var(df_owl$sibling_negotiation)) # 44.50

# the response variable is count data

# variance >> mean

# choice of error distribution = negative-binomal

(m_glm <- MASS::glm.nb(sibling_negotiation ~ food_treatment + nest + offset(log(brood_size)),

data = df_owl))##

## Call: MASS::glm.nb(formula = sibling_negotiation ~ food_treatment +

## nest + offset(log(brood_size)), data = df_owl, init.theta = 0.911083123,

## link = log)

##

## Coefficients:

## (Intercept) food_treatmentsatiated nestbochet

## 0.20011 -0.78129 0.20020

## nestchampmartin nestchesard nestchevroux

## 0.14911 1.02631 0.44853

## nestcorcellesfavres nestetrabloz nestforel

## 1.27423 -0.20826 -2.55492

## nestfranex nestgdlv nestgletterens

## 0.31528 0.24989 0.74728

## nesthenniez nestjeuss nestlesplanches

## 0.52213 -0.63986 0.31026

## nestlucens nestlully nestmarnand

## 0.53563 0.83107 0.56212

## nestmontet nestmurist nestoleyes

## 0.66764 1.01809 0.71780

## nestpayerne nestrueyes nestseiry

## 0.48422 1.15510 0.62465

## nestsevaz neststaubin nesttrey

## 1.73558 0.06776 1.25416

## nestyvonnand

## 0.62720

##

## Degrees of Freedom: 598 Total (i.e. Null); 571 Residual

## Null Deviance: 821.1

## Residual Deviance: 705.4 AIC: 3477Although this model works, it is not advisable. Because there are 27 nests, the model estimates 26 separate parameters, using the first nest as the reference category. This results in an unnecessarily complex model. More importantly, these nest-specific coefficients are not biologically interpretable: comparing one arbitrary nest (e.g., the first) to another does not provide meaningful biological insight, as the data do not encode specific biological differences among nests.

17.2 Random Intercept

17.2.1 Developing a model

Variables included as explicit predictors or explanatory variables are typically referred to as fixed effects. In the previous example, both food_treatment and nest were treated as fixed effects. Fixed effects are usually the primary focus of an analysis, as they represent factors whose effects we wish to estimate directly and interpret in a biological context.

However, as noted above, differences among nests are not biologically interpretable, making them uninformative to include as fixed effects. At the same time, ignoring variation among nests altogether by excluding them from the model would bias the estimated effect of food_treatment.

Random effects are well suited to this situation. They represent categorical grouping variables that assign individual observations to a smaller number of groups. In the example above, nest is an ideal random effect because it groups individual chicks within nests, capturing among-nest variation without requiring explicit estimation of nest-specific effects.

Let’s develop a model that includes nest as a random effect. We will use the glmmTMB() function from the glmmTMB package, specifying the random effect with the syntax (1 | nest).

m_ri <- glmmTMB(

sibling_negotiation ~ # Response variable

food_treatment + # Fixed effect of food treatment

(1 | nest) + # Random intercept for each nest

offset(log(brood_size)), # Offset to model rate per chick

data = df_owl,

family = nbinom2() # Negative binomial distribution

)

summary(m_ri) # Display model results and parameter estimates## Family: nbinom2 ( log )

## Formula:

## sibling_negotiation ~ food_treatment + (1 | nest) + offset(log(brood_size))

## Data: df_owl

##

## AIC BIC logLik -2*log(L) df.resid

## 3492.4 3510.0 -1742.2 3484.4 595

##

## Random effects:

##

## Conditional model:

## Groups Name Variance Std.Dev.

## nest (Intercept) 0.1271 0.3565

## Number of obs: 599, groups: nest, 27

##

## Dispersion parameter for nbinom2 family (): 0.841

##

## Conditional model:

## Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|)

## (Intercept) 0.69378 0.09902 7.006 2.44e-12 ***

## food_treatmentsatiated -0.67769 0.11028 -6.145 7.98e-10 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1Fixed effects still estimate (Intercept) and the effect of food_treatment. The key distinction from a standard GLM is that there are no nest-specific coefficients in the GLMM; instead, the model estimates the standard deviation of the nest effect (estimated as Std.Dev. 0.361), capturing among-nest variation.

The “trick” of GLMMs is to model only the variation between groups as a single random effect (one parameter), rather than estimating a separate parameter for each nest (26 parameters). This substantially reduces the number of parameters, improving model efficiency and increasing the reliability of estimated fixed effects.

17.2.2 Visualize model output

In a GLMM, random effects (e.g., nests, plots, or subjects) are modeled as variation among groups, summarized as a standard deviation in intercept rather than as separate fixed-effect parameters for each group. This means the model estimates how much groups vary around the overall mean, not individual group intercepts directly. We call this specification a random-intercept model because it allows group-specific intercepts.

You can obtain group-specific intercepts using coef() function8 – note that these estimates are show in a log-scale because the negative-binomial distribution uses a log link function:

## (Intercept) food_treatmentsatiated

## autavauxtv 0.3214851 -0.6776889

## bochet 0.4792640 -0.6776889

## champmartin 0.4384421 -0.6776889

## chesard 1.0449504 -0.6776889

## chevroux 0.6627038 -0.6776889

## corcellesfavres 1.0781649 -0.6776889The returned values in (Intercept) represent group-specific intercepts, showing that GLMMs account for group-level variation by allowing the intercept to vary across groups. The coefficient of food_treatmentsatiated is constant across nests because we did not allow variation in this parameter among groups.

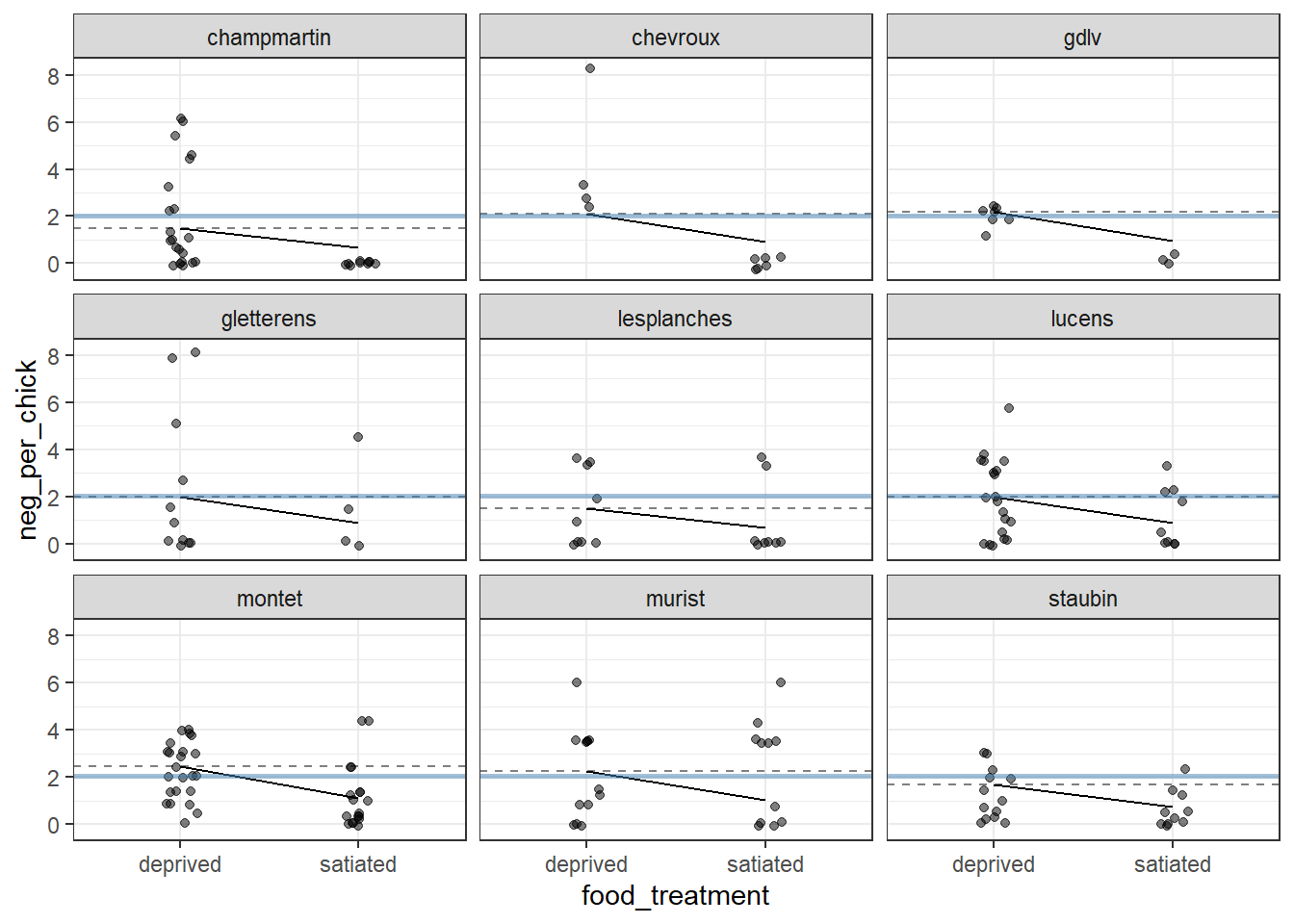

Since plotting all 27 nests would be tedious and hard to track visually, we will use only random nine nests for this visualization.

Figure 17.1: Visualization of a random‐intercept GLMM fitted to owl nesting data for a subset of nine nests. Points show observed counts of negotiation calls per chick. Dashed horizontal lines indicate nest‐specific intercepts (back‐transformed to the response scale from the log link), reflecting baseline differences among nests. Solid line segments connect predicted values under unfed and satiated treatments, illustrating the common (fixed) effect of food treatment, which is assumed to be identical across nests in the random‐intercept model. The solid blue horizontal line represents the global intercept (population‐level mean). Panels are faceted by nest to emphasize between‐nest variation in baseline response.

17.3 Random Intercept and Slope

17.3.1 Adding a random slope term

In the random-intercept model, written as (1 | nest) in the above example, we allow each nest to have its own baseline level (its own intercept) in the number of negotiations per chick. In other words, nests can start at different average values. However, as we saw from coef(m_ri), the effect of food_treatment is the same for all nests—the slope does not change across nests.

This reflects an assumption of the model: while nests may differ in their overall level, the effect of food treatment is assumed to be similar across nests. Any nest-to-nest differences in how food treatment works are assumed to be small enough to ignore.

We can relax this assumption by allowing the effect of food treatment to vary among nests. This is done by specifying the random effect as (1 + food_treatment | nest). In this random-intercept and random-slope model, the model still estimates an average effect of food treatment, but it also allows each nest to have its own slope, capturing differences in how strongly nests respond to the treatment:

m_ris <- glmmTMB(

sibling_negotiation ~ # Response variable

food_treatment + # Fixed effect of food treatment

(1 + food_treatment | nest) + # Random intercepts and slopes for each nest

offset(log(brood_size)), # Offset to model rate per chick

data = df_owl,

family = nbinom2() # Negative binomial distribution

)

summary(m_ris) # Display model estimates and diagnostics## Family: nbinom2 ( log )

## Formula: sibling_negotiation ~ food_treatment + (1 + food_treatment |

## nest) + offset(log(brood_size))

## Data: df_owl

##

## AIC BIC logLik -2*log(L) df.resid

## 3447.0 3473.4 -1717.5 3435.0 593

##

## Random effects:

##

## Conditional model:

## Groups Name Variance Std.Dev. Corr

## nest (Intercept) 0.006385 0.0799

## food_treatmentsatiated 1.215901 1.1027 1.00

## Number of obs: 599, groups: nest, 27

##

## Dispersion parameter for nbinom2 family (): 0.978

##

## Conditional model:

## Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|)

## (Intercept) 0.65330 0.06225 10.496 < 2e-16 ***

## food_treatmentsatiated -0.97408 0.24512 -3.974 7.07e-05 ***

## ---

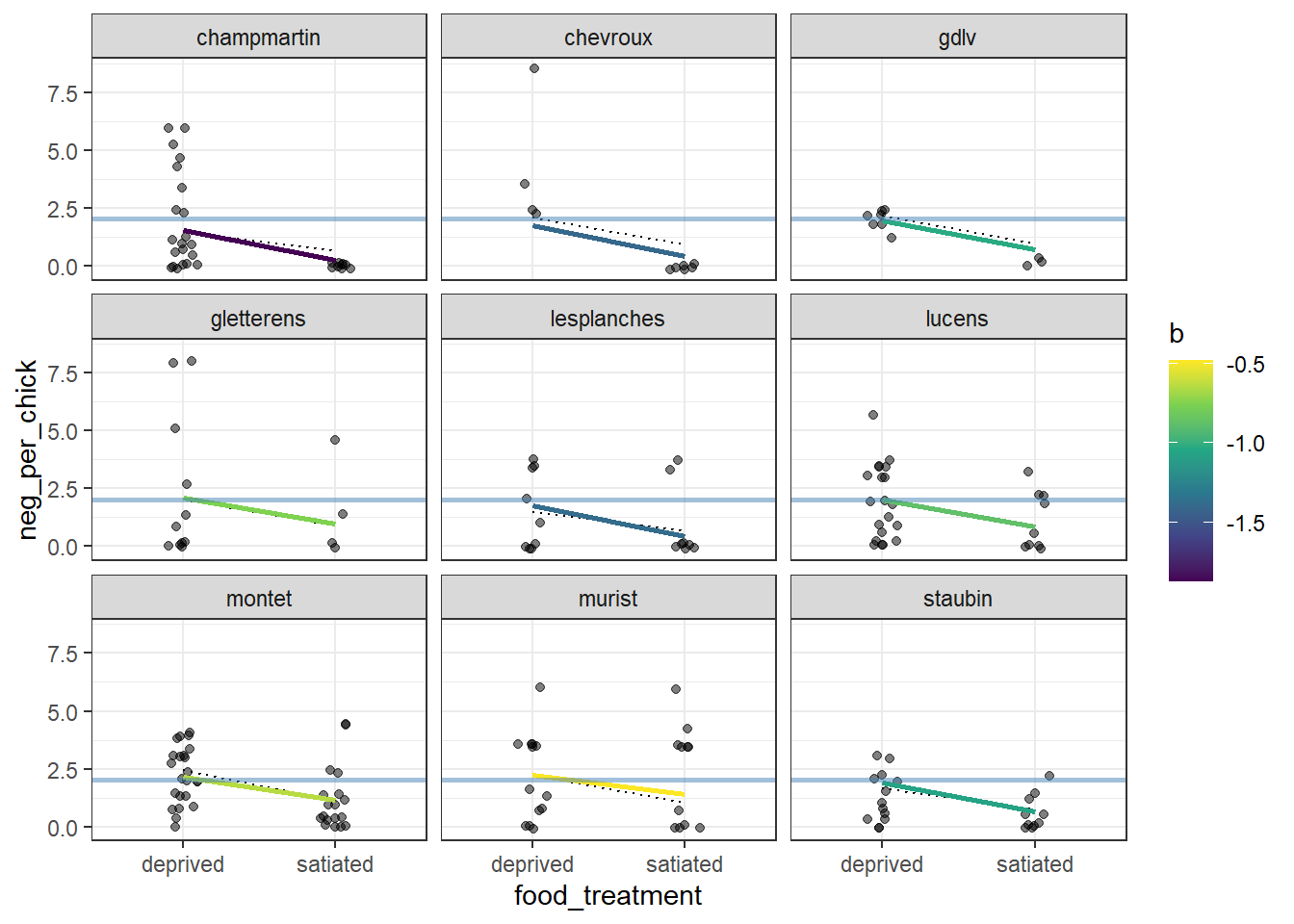

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1Now, coef(m_ris)$cond$nest returns variable slopes among nests, reflecting the assumption of the random slope:

## (Intercept) food_treatmentsatiated

## autavauxtv 0.6458989 -1.076110554

## bochet 0.5818570 -1.960248712

## champmartin 0.5051865 -3.018403203

## chesard 0.7381005 0.196113330

## chevroux 0.5486965 -2.417926598

## corcellesfavres 0.7235323 -0.004790489Again, visualization helps clarify how this model differs from the random-intercept model. In the random-intercept case, lines for different nests are parallel, because the effect of food treatment is the same across nests.

The following highlights how the effect of food treatment differs among nests by allowing each nest to have its own slope. As a result, the lines are no longer parallel, making it easy to see nest-specific responses to the food treatment.

Figure 17.2: Visualization of a random‐intercept and random‐slope GLMM fitted to owl nesting data for a subset of nine nests. Points show observed counts of negotiation calls per chick under each food treatment. Dotted line segments represent predictions from the random‐intercept model, where the effect of food treatment is assumed to be constant across nests. Solid line segments show predictions from the random‐slope model, allowing the effect of food treatment to vary among nests; color indicates the nest‐specific slope estimate. The solid blue horizontal line denotes the global (population‐level) intercept. Panels are faceted by nest to emphasize differences in both baseline response and treatment effects.

17.4 Fixed vs Random

In statistical modeling, particularly in ecology, factors in a dataset can be treated as fixed effects or random effects. Choosing the appropriate type affects how we interpret model coefficients and account for variation in the data. Fixed effects are used when we are specifically interested in estimating and comparing the levels of a factor, while random effects are used when the levels represent a sample from a larger population and we are primarily interested in quantifying variability among them.

| Type | Interpretation | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Fixed effect | You are explicitly interested in the slope of specific levels of the factor or of continuous variable. Can be categorical or continuous. | Nutrient treatment (ambient vs. added), Sex (male vs. female), Temperature (continuous) |

| Random effect | The levels are a sample from a larger population. You are not interested in estimating each level, but rather in modeling variation among them. Must be categorical. | Nest ID, Site, Year, Block, Individual ID |

17.5 Model specification

17.5.1 Random intercept

With \(y_i\) denoting the number of negotiation calls (sibling_negotiation), the above example is formulated as follows:

\[ y_i \sim \mbox{NB}(\mu_i, \theta)\\ \ln \mu_i = \underbrace{(\alpha + \gamma_{j(i)})}_{\text{intercept + random effect term}} + \underbrace{\beta}_{\text{slope}} x_i + \ln(\mbox{offset term})\\ \gamma_j \sim \mbox{Normal}(0, \sigma_{\gamma}^2) \]

Here, \(i\) indexes individuals, and \(j(i)\) denotes the nest to which individual \(i\) belongs. In our model estimates, global intercept \(\alpha\) = 0.69, effect of food treatment \(\beta\) = -0.68, dispersion parameter \(\theta\) = 0.84, and SD of the random effect \(\sigma_{\gamma}\) = 0.13. Although this example uses a negative binomial model, the overall structure is similar for other probability distributions, provided an appropriate link function is chosen.

17.5.2 Random intercept and slope

With the random slope term, the model specification becomes:

\[ y_i \sim \mbox{NB}(\mu_i, \theta)\\ \ln \mu_i = \underbrace{(\alpha + \gamma_{j(i)})}_{\text{intercept + random effect term}} + \underbrace{(\beta + \delta_{j(i)})}_{\text{slope + random effect term}} x_i + \ln(\mbox{offset term})\\\]

When a random slope term is included, random intercept and slope terms are assumed to follow a multi-variate normal distribution, specified as:

\[ \{\gamma_{j}, \delta_j\} \sim \mbox{MVN}(0, \Sigma) \]

where \(\Sigma\) denotes the variance-covariance matrix of random effect terms.